Introduction to Apache Kafka

In my previous blog I wrote about distributed systems and why we choose this path with today’s requirements. One of the most important parts of a scalable architecture is a messaging system which is used for communication of application components, log aggregation, event handling, etc. There are some standards that try to describe different protocols but I will focus on the architecture.

Typically, we use publish-subscribe message brokers to handle our message queue and this is a great way to start. The logic behind this is that everything is an event and all the components either produce or consume events. It’s always easy to expand functionality, to add more publishers or subscribers and even base an architecture on events (event-driven architecture). There is a lot of material describing these concepts so I will not get into detail. The problem I’m focusing on is scalability and performance.

One of the crucial parts of any system is data ingestion, especially if it has peaks (as it usually does) and the amount of messages is moderate to high (more than 20k/s). In this case, the typical publish-subscribe broker systems are lacking performance and easily become hot-spots. Some of the broker implementations do scale but there are some conceptual problems. These problems are something that engineers at Linkedin solved with Apache Kafka. They solved the problem of a typical publish-subscribe system by implementing it as a commit log. What does this mean?

Lets look at the [RabbitMQ][rabbit-mq-link{:target=”_blank”}] which is a great implementation of a messy AMQP standard and works great as a distributed message broker. It’s robust, provides good overall performance and the cluster is transparent to the client. It really does a good job for the use case it’s built for. One of the key concepts is what requires a change. RabbitMQ (and most of the message brokers) presume by design that consumers are mostly online and messages in queue, which are waiting to be consumed, are held opaquely. It is simply not designed to persist large amounts of messages on the broker.

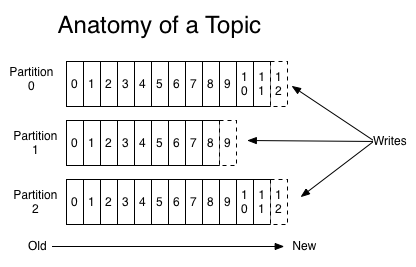

Apache Kafka was conceptually designed to partition and persist large amounts of messages disregarding if the consumers are online or not. Kafka presumes that producers generate messages at such a rate that it can be thought of as a stream. Main point is not to throttle down producers because consumers are failing to consume data fast enough but to provide a buffer between the flood of events and the system/consumers. Consumers in this concept can process events at their own pace either online, in batches or even offline. One of the key advantages is that Kafka partitions messages based on topic and across nodes and provides ordered delivery within a partition. AMQP standard defines that one of each producer, channel, exchange, queue and consumer are required for ordered delivery. This breaks the philosophy of no single point of failure.

One of the important features with decoupled producers and consumers is that messages can be read on demand and at a consumer’s pace. Kafka provides the ability to replay events that enables fallback scenarios in fast data stacks with NoETL approach. This is possible because messages are persisted in Kafka for a configurable period of time whether they have been consumed or not.

Positions of a consumer in the partition are saved in the cluster but the consumer is responsible for changing this position (offset). At any given time, the consumer can decide to replay all the events in a partition. Partitioning itself provides a great way to scale on multiple nodes but one partition must fit on a single node. Topics on the other hand are partitioned and can span multiple nodes. Messages are consumed in two different ways. The first one is queue where we have a pool of consumers and each message is consumed by one of them. The second one is publish-subscribe where messages are being broadcasted to all of the consumers.

Kafka provides a couple of important guarantees. Message ordering is preserved based on a producer and consumers see these messages in the same sequence as they were produced. Replication is defined by replication factor and there is a fault tolerance for up to N-1 server failures. Kafka can guarantee “at least once” delivery semantics per partition.

When looking at the performance, Kafka can sustain 1mil of messages produced per second on just a couple of nodes keeping the durability and ordered partitioning of data. This performance is considered high and only the top few companies have higher requirements than this.

One of the down-sides is complexity as in any other distributed system. Kafka requires Zookeeper to run in order to keep nodes in sync. I’m not a fan of single point of failure spots in distributed systems, like Zookeeper is, especially when we introduce additional complexity in order to solve single instance problems but then again rely on something like Zookeeper to keep things running.

Being distributed, Kafka has failover mechanisms where if master node is down, one of the existing nodes is automatically voted and promoted into master. Scalability is one of the key features and this is where Kafka excels and with a fault tolerance of RF-1 (Replication Factor) nodes it is a great choice for the backbone of data intensive system. When opting for Kafka keep in mind that there aren’t many drivers outside the JVM stack at this point and that you need to run a cluster of nodes in order to benefit from fault tolerant replication. If you need to push large messages or if simplicity and ease of use is what you are after you should consider some of the lightweight brokers, but if you need reliability and performance at scale and are pushing large amounts of data through your system then Kafka is the perfect choice.